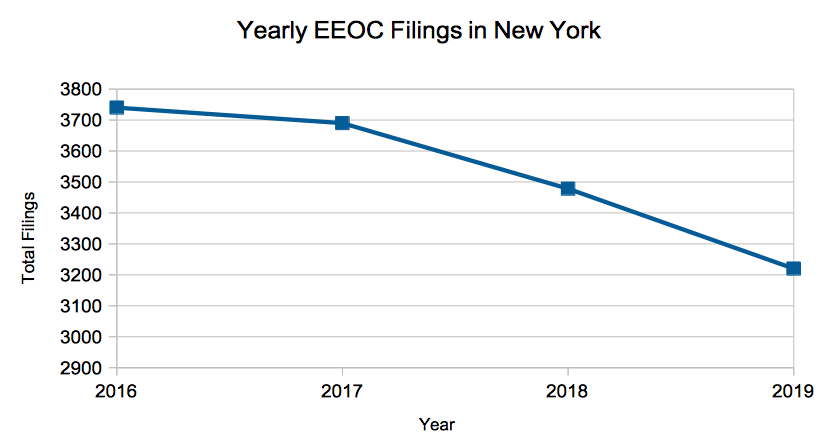

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is the federal agency charged with investigating and prosecuting claims of discrimination arising under federal law. Generally, federal law prohibits workplace discrimination on the basis of sex, race, national origin, religion, color, disability, age, and genetic information. Further, federal law prohibits employers from retaliating against employees who report or…

Continue reading ›Your Side